Snow can be defined as precipitation in the form of small white ice crystals formed directly from the water vapour in the air. Usually, Mother Nature is responsible for providing the goods that are lusted after by skiers and boarders the world over. But when Mother Nature doesn’t deliver and commercial resorts need snow, that’s when the Snowmakers step in.

Manmade snow was accidentally discovered back in the 1940s when Dr. Ray Ringer and his team were studying the effects of rime icing on the intake of a jet engine in a low-temperature lab here in Canada. Inside a wind tunnel, the researchers were attempting to recreate natural conditions by spraying water just in front of the engine. They weren’t able to replicate the rime ice, but they did make snow. Then in 1950, the first snowgun was created by Wayne Pierce, Art Hunt, and Dave Richey in response to a snow drought that was negatively affecting ski sales. They determined that by blowing water droplets through freezing air, the water would freeze into snowflakes. With some mechanical ingenuity, they turned a paint spray compressor, a nozzle, and some garden hose into the original, albeit rudimentary, snowgun.

Two years later, Grossinger’s Catskill Resort Hotel, located in the Catskill Mountains near Liberty, New York, was the first to use artificial snow anywhere in the world. The practice of snowmaking gained momentum through the ’70s with many ski resorts employing the use of artificial snow to increase the length of their seasons. Modern snowguns have come a long way from that original design. They are now state-of-the-art machines, boasting onboard weather stations, adjustable nozzles, and software that can maximize output even with subtle changes in temperature and humidity.

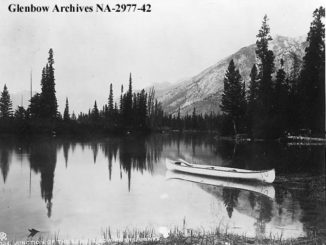

The practice has fascinated me ever since I saw a snowgun in action, years ago when I was learning to snowboard. I approached the Lake Louise Ski Resort to see if they’d be interested in collaborating on a snowmaking story for my Wild Jobs column. Thankfully, Matt Dunphy, the Snowmaking Supervisor was more than happy to talk about his career path thus far. Matt first arrived at Lake Louise in 2010 where he was employed as a Snowmaker. He transitioned to Assistant Supervisor after his initial season and was in that role for three years before moving into his current position. Prior to working for Lake Louise, Matt had never worked in the ski industry before, but he hasn’t let that minor detail slow him down. What follows is an in-depth look at what it takes to make snow at one of the largest winter resorts in Canada, that also happens to be located within the boundaries of Canada’s flagship national park.

Calgary Guardian: “Where are you from? What brought you to Lake Louise?”

Matt Dunphy: “I originally hail from Millbrook, Ontario, a smaller farming community just outside of Peterborough, Ontario. Having left there and deciding to come west, I had begun working for Parks Canada in Northern Saskatchewan. After the course of a couple seasons, though, I realized just how miserable and bleak of an experience it was to endure a Saskatchewan winter. I had decided pretty early-on to make my escape. Luckily, a snowmaking job presented itself at Lake Louise Ski Resort, and I figured an escape to the mountains was as good an option as any, and hoped it would prove to be something a little more hospitable and fun. Thankfully it was.”

CG: “What equipment is needed for making snow?”

MD: “It all starts with a supply of air and water, which are provided from our Primary and Booster pump-houses. Large pumps push water into a variety of pipelines up the mountain to an adequate pressure which are subsequently accessed through hundreds of water hydrants, scattered throughout the mountain. Air is also provided, though instead of pumps, large compressors are responsible for charging air into a network of pipelines, similarly feeding a variety of air hydrants. Access to these hydrants requires substantial amounts of hose, typically 100 ft. long fire-hose, rated to high pressures. The only other essential equipment for a snowmaking operation are snowguns. These can come in a variety of styles and designs, but essentially breakdown into two categories: fanguns and air/water guns. Both are hooked up to water hydrants with hose, but only air/water guns require air hydrants. Unlike air/water guns, fanguns are run electrically, and are fitted with their own small, onboard compressors that provide air. Obviously, there are a few auxiliary/optional pieces of equipment that we use, which depend on the unique circumstances of each ski-hill’s operation. These include things like diesel generators, which provide power to fanguns in areas that are out-of-reach. In a nutshell, if you have these essential pieces of equipment, then you have the means to make snow.”

CG: “Are there specific weather conditions needed for making snow?”

MD: “It all relies on a number of factors, which can include a combination of the relative humidity, wind, the temperature of your water supply, and even variations in the difference between an overcast day and bluebird day. Traditionally, in my experience, we can depend on reasonable success with a wet-bulb temperature from -2°C to -2.5°C. At these temperatures, you can begin to see a measurable accumulation of snow production. Although, this is not always the case and is more of an exception to the rule – it’s actually possible to make snow in temperatures above the freezing point. The concept there is that marginal temperatures can actually cool a few degrees due to evaporation. Unfortunately, in my experience, I can’t speak to having any success in being able to do so.”

CG: “What type of educational background is needed for your job?”

MD: “Although it is not an officially-mandated requirement, ideally, a mechanical or electrical background goes a long way in this job. Especially considering the extensive use of compressors, pumps, and generators for day-to-day operation. Snowmakers themselves are not required to have these skills, however with their day-to-day responsibilities they are nice skills to have. Luckily, we are blessed at the Lake Louise Ski Resort with a strong, supportive relationship with the affiliated skilled-trade departments, like Electricians, Mechanics, and Millwrights, who understand the operational importance of snowmaking production – especially in the early season, where the success or failure of our business relies heavily on an adequate amount of man-made snow. There is a real emphasis on minimizing any potential downtimes, and any/all major issues are usually resolved by this close-knit team, who are always on-call to offer support and problem-solve. But the know-how of addressing breakdowns and mechanical issues is a real asset, with a wide-ranging variety of things able to go south on any given day.”

CG: “Creating man-made snow seems like a pretty technical process. Could you walk me through what that process looks like?”

MD: “The actual physical process of making snow is quite simple. Under the appropriate temperatures, water and air are all that is required. The water leaving snowguns is pulverized by compressed air through a mechanism called a nucleator, which is fitted to most all snowgun models and types. The colder it gets, the less relevant an air element becomes, as there is an atmospheric reduction in humidity and overall air temperature, which in turn allows a water molecule to crystallize into a snowflake more quickly. The technical-side of a snowmaking operation is the more complicated aspect of the job. Equipment, infrastructure, and the management of an adequate air and water supply is an in-depth process that involves constant maintenance and supervision in order to function properly.”

CG: “How is it determined when, where, and how much snow is made? Is it typically early season and times of drought?”

MD: “When your operation is under strict water-usage regulations and conditions like ours is (Lake Louise Ski Resort is located inside Banff National Park, and subject to an operating agreement under Parks Canada guidelines), snow-equivalencies are everything when you are trying to be efficient and lean. In short, we try to produce more snow in areas of higher skier-traffic, especially those with steep pitches that can washout and thin over time. You also have to consider other factors as well, like areas that are more exposed to sunlight or have designated multiple uses, like Terrain Parks, learning-areas, and race-training. Experience with the resort you work at goes a long way, as you have first-hand knowledge of the individual needs of your mountain and identifiable year-to-year trends. The long answer is a more drawn-out process with something called snow-equivalencies, which are basically calculations that are made based on the length, width, and unique terrain of specific ski-runs. Under this concept, snow production and snow-depth are measured in gallons of water per Acre–Ft. Those runs that have a higher number of acre-ft. receive more snow than areas with lower ones. Again, it all depends on the specific needs of each area, and there are exceptions to the rule, but overall, that’s basically how it works.”

CG: “Do you keep track of how much snow you make in a given season?”

MD: “In a sense, yes, we do – that’s also a pretty simple process. Usually, pump-stations are fitted with flow-meters, which track the amount of water being pumped in gallons per minute (gpm). This data is logged in real-time and stored in a tracking system, which can be reviewed throughout an operation. We are no different here, and have on-duty plant operators 24 hours/day, who along with pumps, compressors, online snowguns, and other key system information, monitor this data and organize it into accessible reports for future reference. Once overall gallons are calculated, we can cross-reference this with the number of guns/hydrants that were online during a certain duration on individual runs, which we also track minute to minute during operation. We can then convert the gallons pumped to the aforementioned acre-ft. metrics as well, and this gives an overall indication of snow volume. Again, there are exceptions that affect the accuracy of your calculations, such as factoring in things like temperature at the time of production and after. This can alter exactly how much water is actually being converted to snow. Cold temperatures can translate to water being lost to the atmosphere, while warmer temperatures can mean water not being crystallized into snow at all.”

CG: “Snowguns are pretty big pieces of equipment. Are they moveable to different areas of the resort or are they stationary?”

MD: “There are two variations of a fanguns, which come in ‘tower’ and ‘mobile’ varieties. Tower fanguns are permanent, and are therefore strategically-placed in areas which require a repeated, high-demand for snow. Mobile fanguns, however, are designed to be moved, and are done so often and quite easily by snowcats. Most designs come with attachments that allow them to be lifted and carried on the blade of a snowcat, and they can be placed virtually anywhere within the range of a power source.”

CG: “What’s the best part of your job?”

MD: “Most snowmakers would probably mention the more obvious perks of the job, which are mainly being able to work outside all day, or the bonus of being able to ski/snowboard on the clock. Both of these things are great and certainly worth being appreciated, especially in as beautiful a setting as Lake Louise. But for me, there is a certain satisfaction with being able to track your progress in real-time. Under ideal conditions, like when it’s cold out, and the snowguns and system are working as they should, you can literally watch the piles of snow grow hour by hour – there’s no mistaking how well (or poorly) you are doing. That’s not something a lot of people can say about their own jobs. It’s a very rewarding process knowing that everyone else can see your hard-work and progress too. The flip side of that, of course, is that it can be crushing and obvious when things aren’t going so well, so it’s a double-edged sword I suppose. But just the idea of seeing how your hard-work is translating to a tangible progress in real-time – right before your eyes – is definitely rewarding.”

CG: “What’s one of the most challenging aspects of your job?”

MD: “When October and November rolls around, it’s always a challenging time. Snowmaking at the Lake Louise Ski Resort requires undertaking quite a large number of responsibilities in the earliest stages of the season. Our obligations to simultaneously build a downhill race course for the FIS World Cup and create an adequate amount of production for an opening of the first ski-runs to our guests requires a significant amount of coordination and pushes our system, staff, and management to the limits of their abilities. The condensed timeline of being able to achieve success on both fronts can sometimes be overwhelming, but the reward is all the more sweet when we pull it off.”

CG: “Is there anything else you’d like to add about your job that I might have missed in the previous questions? Anything that would give a clearer picture of your job and what it entails?”

MD: “As a day-to-day job, snowmaking is really a unique one and I’m always glad when the opportunity arises to discuss it and describe it to anyone interested. The technical aspects of the job aside, it’s not always for everyone. At times, depending on the shift you punch into, it can be physically-tolling and there is definitely a manual labour requirement there that most people don’t always consider. But luckily, in my experience, the job tends to attract the type of person where these things don’t matter. I always remind my staff that although their job title may be ‘Snowmaker’, it is actually the guns that make the snow. It’s their job to make sure those guns can do their jobs under the best possible circumstances, whether that be cleaning them off, adjusting them properly, and so on.”

It cannot be a coincidence that the first artificial snow was created here in Canada, even if it was by accident. We have an international reputation of being a cold, desolate place (even if we all know better), so it seems appropriate that we were the ones responsible for making something that the rest of the world assumed we already had enough of. Especially in times of drought, all of the skiers and snowboarders that visit resorts around the globe each winter, are thankful for its invention.

I would like to take this opportunity to thank Matt for his thoughtful responses to all of my questions. He did a wonderful job of explaining the technicalities of snowmaking in terms that were easy to understand and follow. I know that adding one more thing to your already busy schedule wasn’t easy, but I do appreciate your time and insight into your unique career. I also want to thank Sarah Magyar, the Content Supervisor for Lake Louise Ski Resort, for arranging this interview. It wouldn’t have been possible without you.

To stay up to date with everything happening at Lake Louise, please visit their website. You can also stay connected with them on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, and Pinterest. For even more winter resort Wild Jobs, please see my past stories about Avalanche Dogs, Mountain Safety Teams, and Lift Operators. I have also collaborated with Lake Louise on stories about Snow School Instructors, Snow Groomers, and even one about their Summer Gondola.

***

About this column:

Wild Jobs is a running series that focuses on people in outdoor-related professions. It provides a brief snapshot of their career and the duties that it entails. Please see my previous post, Wild Jobs: Cat Ski Owner and Guide to learn more.