“It had been a long day. Ed’s fifty-seven winters combined with the warm sun of later afternoon weighed heavily on his eyelids, so he drowsed in the saddle, riding with a slack rein. Sometimes he loosed his right leg from the stirrup and let it trail free, because the chunks of steel-jacketed lead the Army doctors had overlooked pinched the nerves at times, making it painful to bend his knee. Now and again the horse, sensing its rider was dozing off, would stoop to steal a mouthful of grass along the way, but mostly it stepped along quick enough, headed for the cabin and a bait of oats. Ed’s dog Willie, a six-month-old collie pup, ran along under the stirrup. Ed trusted the horse. It was a seasoned animal that knew the country well and knew the dangers too. They had seen a silvertip earlier that day, feeding on the broad leaves of cow parsnip at the edge of a small meadow near the trail, but Ed had passed it off as just another grizzly. The horse had never run from a bear before. This time, though, it must have come on to the bear sign too fast, or perhaps the wind changed suddenly and the horse go too much bear stink all at once, because it suddenly shied violently, and Ed, not having a good seat, with one leg out of the stirrup, found himself flying off before he could gather rain. He lighted on his back, right on a dead tree that lay beside the trail. Something gave with a snap that made him yell with agony and, winded, he lay still, wondering what had hit him. Before he could move, the hose came by him, bucking, and kicked him hard on the hipbone. Still unaware of how badly he was hurt, in the numbness that sometimes follows a serious injury, Ed tried to get up, but found he could not stand. His pelvis was broken.”

~Sid Marty from Men For The Mountains

The vivid scene, so eloquently written by long-time warden Sid Marty, showcases the stark contrast of the warden lifestyle perfectly. First we have the romanticized version; a man alone in the remote wilderness, sitting low in the saddle after a long hard day, the sun setting on his back as he rides to a backcountry cabin for some well-earned shuteye. We imagine birds chirping, leaves rustling in the breeze, and a brook babbling nearby. The idyllic scene quickly evaporates as the dangers of the job explode onto the page. An unseen and unexpected encounter with a surprised bruin left this particular gentleman badly injured, but he survived to tell the tale. The story above is from the late 1930s, but that image of a lone warden patrolling outlying borders has persisted for decades, despite their roles radically evolving over the years.

The Warden Service has been in existence for over a century. The person first appointed to the role of warden (known as Forest Rangers at the time) was John Connor, back in 1887. In those early days their main concerns were with fire suppression and game management. Over twenty years later, in 1909, the warden service was officially realized by the Department of the Interior. Permanent positions were created, luring some of the most famous characters the warden service ever produced, such as ‘Wild’ Bill Peyto. As tourism in Canada’s west increased, so too did the responsibilities of the wardens. Search and rescue became more apparent, as did trail building and maintenance. A series of backcountry cabins were erected to assist on those long patrols searching for illegal hunters and poachers. Even public relations became more commonplace. Wardens were a remarkably knowledgeable bunch, so visitors turned to them for their expertise of the natural world. Today, law enforcement plays a substantial role in the duties of Park Wardens, and an increasing amount of their time is spent in the park’s most frequented locales, instead of those sought-after remote confines. Although the job description has repeatedly changed, they are still the guardians of our wildest places.

To get a better idea of the work of a modern-day Park Warden, I reached out to Parks Canada with the hope of securing an interview. As you’ll soon discover, I was not disappointed with the results. What follows is an in-depth conversation with a Park Warden stationed in Banff National Park. They paint striking images with their words and you’ll be transported to some of the most stunning landscapes this country has to offer. I hope you revel in this profile of one of the most fascinating professions I have had the pleasure of featuring in this column. Enjoy!

Calgary Guardian: “What is your official job title? Are you still called ‘wardens’ because terms like ‘ranger’ and ‘conservation officer’ also get used frequently?”

Park Warden: “Our title is ‘Park Warden’. Historically, this title was held by many employees of the Parks Canada Agency whose responsibilities included visitor safety, fire management, law enforcement, and ecological monitoring. About 10 years ago, functions became far more specialized, and now only those working with Parks Canada in Law Enforcement hold the Park Warden title.

CG: “Have you always worked in Banff National Park or were you previously in other national/provincial parks?”

PW: “I’ve worked in several resource enforcement and resource management positions with other government agencies prior to my current position with Parks Canada. There are so many fascinating places to explore in this country, and so many interesting communities to work in. I’ve fought fires in Quebec, trapped bears in Manitoba for research and monitoring purposes, pursued sheep poachers in Alberta, attended training in Ontario and Saskatchewan, and pulled noxious weeds in British Columbia. Each position has allowed me to support good stewardship of our country’s natural resources.”

CG: “Why did you want to become a Park Warden?”

PW: “I am continually astounded by nature. The intricacies and adaptations of every plant, fish, bird, and animal on our landscapes are incredible. The viewscapes are also spectacular. I strive to protect the natural environment through education, prevention, and enforcement so that our generation and those to come can enjoy it as much as I do. The work is interesting too. There are quite a few mandatory, consistent tasks, but the job is also a new adventure everyday! We can tailor our day to the weather, the season, the issues of the day, and our desired mode of transport. This can include patrols by vehicle, bicycle, touring and cross country skis, boat, helicopter, horse, and of course by foot.”

CG: “Are you originally from Alberta? If not, what brought you to this province?”

PW: “I’m not a born and raised Albertan, but I’ve learned through my many vocations in a variety of locations that each of Canada’s places has its own remarkable uniqueness.”

CG: “What type of education/training/certification do you need to become a warden?”

PW: “The educational requirements for the position include successful completion of post-secondary education with a diploma or degree in a field related to conservation, natural resource enforcement, law enforcement, natural resource management, or environmental science. Recent experience working in the natural environment in a job related to resource conservation, law enforcement and/or education is also required. Those applying for this position also require several certifications such as first aid.”

CG: “What is the best thing about your job?”

PW: “The best thing about my job is the people and the landscape. My coworkers here are passionately dedicated to conservation, and the most polite, welcoming, friendly people I’ve worked with. The natural world is pretty incredible too. I spend a lot of time outdoors and the mountains, sky, and landscapes are different and breathtaking every single day.”

CG: “What is one of the most difficult things about your job?”

PW: “In Banff National Park, we receive over 4 million visitors per year. The call volume and work load for the Law Enforcement Park Wardens can be very high. Some situations we have to deal with are stressful, and shift work can be tiring. Finding a balance between work and life outside of work, managing responsibilities, exploring new solutions to address ongoing issues, caring for ourselves and supporting our colleagues are all important for long term success.”

CG: “It seems as though wardens wear a lot of different hats during the course of their careers. Could you describe some of the varied responsibilities that wardens have?”

PW: “Our authorities are similar to those of the RCMP; however, our focus is on the Parks Canada mandate. We strive to protect our cultural and natural resources for current and future generations.

Wardens have to be able to hike up mountains and along windblown ridges to patrol the park boundary for hunters, ski for miles carrying a heavy pack in frigid temperatures to check backcountry shelters, slog through mosquito infested woods searching for illegal campers, and ride a horse through wild country and treacherous terrain to access backcountry sites.

We conduct proactive patrols to detect offences and must be intimately familiar with all of the legislation we enforce to ensure that in each situation we respond appropriately.

We respond to public reports and initiate investigations, collect evidence, and depending on the situation, we engage with suspects, interview witnesses, and determine if charges are warranted.

We occasionally lay charges, then carefully compile files and communicate with the Crown Prosecutor. We attend court to testify in trials, present evidence and educate the judge or justice on the intricacies of the Canada National Parks Act and regulations.

We encounter people experiencing social and mental health issues, and must respond effectively to each person and event, acting in a calm, fair, and professional manner no matter how we are treated, always ensuring the rights of that person are protected in accordance with the law. We may deal with people who have a history of violence, active warrants, or who possess weapons or drugs, while ensuring our, and the public’s, safety.

We act as an information source to the public, providing directions to the nearest washroom, identifying flora and fauna and explaining the biology of it, or educating visitors on how to keep a clean campsite that does not attract wildlife.

We work days, nights, weekends, and statutory holidays, sometimes at the expense of our families and social life because we firmly believe in protecting our resources. Being a Park Warden isn’t ‘just a job’, it’s simply our way of life. The work is always varied and interesting.”

CG: “After hearing all of that, I am positive that a ‘normal’ day doesn’t exist in your line of work, but could you provide a rundown of what a typical day at the office might look like for you?”

PW: “Great question! The best part of this job is the unknown. Every day is different, and we can’t predict what might happen next! We do try to focus on current closures or restrictions, parking issues, areas where people frequently illegally camp, or areas where hunters might enter the park, depending on the season. A day could be filled with bush-wacking around the town site to locate illegal campers, checking anglers to ensure they have proper licenses, interviewing visitors involved in an accident, stopping a vehicle exceeding the speed limit, flying or riding horses to the Park Boundary to check for hunters, skiing to backcountry shelters, biking to mid-country campsites to check permits, dealing with people who have left garbage and attractants that wildlife feed on, taking the stand in the Court Room to testify, providing presentations to new staff, and of course, trying to finish all the paperwork that goes along with these adventures.”

CG: “What is one of the most memorable experiences you’ve had while on the job?”

PW: “There are so many! My favourite days are during the fall when we conduct nine-day backcountry boundary patrols looking for hunters. A typical scene would be a warm fall day with deep blue skies, listening to the creak of my saddle as I ride my horse through an old forest fire. The skeletons of burned trees shine silver and bronze where the blackened bark has peeled off. The bog birch and willow leaves are an array of bright red, orange, and yellow, and the fluff from fireweed seeds floats through the air. Hundreds of sheep graze along the alpine slopes above me, and I’m following a trail that’s been beaten into the ground by centuries of travelers, observing the tracks of elk, bear, wolves, and marten that have passed before me. Golden eagles circle above as they make their way south along migratory routes while a bull elk’s bugle echoes through the valley. Moments like these rejuvenate me after a summer of dealing with illegal campers and dogs off leash.”

CG: “I’m not asking you to give away any of your top-secret locations, but do you have a favourite place in Banff National Park? What makes it so special?”

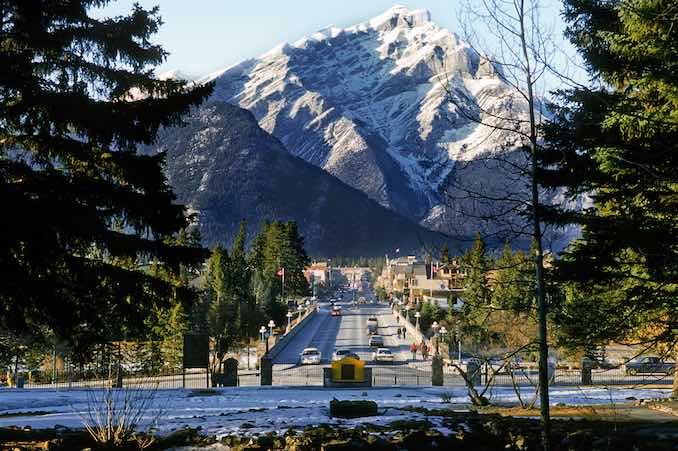

PW: “There are some special places that are easy for the public to access. A simple ten minute hike up to the bottom of Cascade Falls offers an easily attained, lofty view of the Bow Valley and townsite. A bike ride or walk along Vermilion Lakes road delivers incredible mountain panoramas that are reflected on the water, and a plethora of bird species are evident throughout the summer months. In the winter, herds of elk or packs of wolves travel across the ice. A tour of the Bow Valley Parkway, the golf course, or up to the Norquay Road viewpoint almost always provide wildlife viewing opportunities.”

CG: “I know Banff is enormous, but is there a place in the park you haven’t been to that you’d really like to see? If so, where is that?”

PW: “Banff National Park is 6,641 square kilometers with endless opportunities to explore. My duties typically keep me in the vicinity of the Bow Valley and the townsite, which is where the majority of the visitors are. We have backcountry patrol cabins located throughout the park, approximately one travel day apart. I’ve been to several of these but there’s so many left to explore. Parks employees have been using these cabins and the trails in between since the Banff’s inception, but trails and campsites date back more than 10,000 years. It’s fascinating to travel to these places that have been used for so long.”

CG: “Is there any advice you’d give to someone who might be interested in a career as a Park Warden?”

PW: “I’d encourage them to meet a warden! We are based in parks across Canada and are always keen to share information about our jobs and employment requirements with those who are interested.”

The warden’s job is not a seasonal one and summer’s in our national parks, especially one as popular as Banff, are extremely busy. With that in mind I would like to extend my utmost gratitude to this warden for taking the time to thoroughly answer all of my questions. It goes without saying that this glimpse into the life of a Park Warden wouldn’t have been possible without you, so for that I say thanks! I would also like to thank Carly Wallace, the Public Relations and Communications Officer for the Banff Field Unit with Parks Canada, for connecting us. Without that link the above story wouldn’t exist. Thank you for all the behind-the-scenes work to make this a reality.

For all relevant information about Parks Canada please visit their website. You can also connect with them on any number of social channels, such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube. Banff National Park also has their own specific social accounts on Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube for you to follow.

***

About this column:

Wild Jobs is a running series that focuses on people in outdoor-related professions. It provides a brief snapshot of their career and the duties that it entails. Please see my previous post, Wild Jobs Part Nineteen: Cave Guide to learn more.