High in the Selkirk Mountains, the glaciers of Mount Revelstoke and Glacier National Parks have long captivated scientists, climbers, and travellers alike. But beyond their breathtaking beauty, these rivers of ice hold vital clues about our planet’s changing climate. Glacier monitoring in these parks has been underway for more than a century, dating back to the late 1800s, when some of the first photographs and measurements were taken near the Illecillewaet Glacier, one of Canada’s most studied icefields. These early records, collected by surveyors and explorers, laid the groundwork for one of the longest continuous glacier monitoring programs in North America.

Today, Parks Canada researchers continue this legacy, using a combination of historical photography, satellite imagery, and field surveys to measure changes in glacier size, depth, and melt rates. This work is more than scientific curiosity; it’s a concerted effort to understand how a warming climate is reshaping Canada’s mountain landscapes. Glaciers act as natural water reservoirs, feeding rivers and ecosystems downstream. As they shrink, they signal shifts in water availability, ecosystem balance, and even natural hazards like floods and landslides. Monitoring these ancient ice masses helps scientists forecast future environmental changes, guiding conservation and adaptation strategies not only for the mountain parks but for communities across western Canada and beyond.

In honour of the International Year of Glaciers’ Preservation, I have been on a mission to learn more about these ancient sheets of ice, especially the ones here in Canada’s western provinces. I connected with Parks Canada staff about a Wild Jobs instalment focused on glacier monitoring in Mount Revelstoke and Glacier National Parks. They were very keen to collaborate and I was able to interview Michel Beauchemin, who is a Resource Management Officer. Michel is an avid backcountry skier and mountaineer who studied biology, physical geography, and ecology in Québec before moving to British Columbia 19 years ago. Michel has been with Parks Canada for 15 years and has worked in visitor services, ecological integrity monitoring, wildlife monitoring, environmental surveillance and human-wildlife coexistence. What follows is a detailed look at the work being done in two of our mountain national parks around glacier monitoring and fieldwork.

I understand that Parks Canada does not have a Glaciologist working directly for them; however, there are Glacier Fieldwork Team Members employed by Parks Canada to assist in glacier-based research and monitoring. What type of work do these team members engage in?

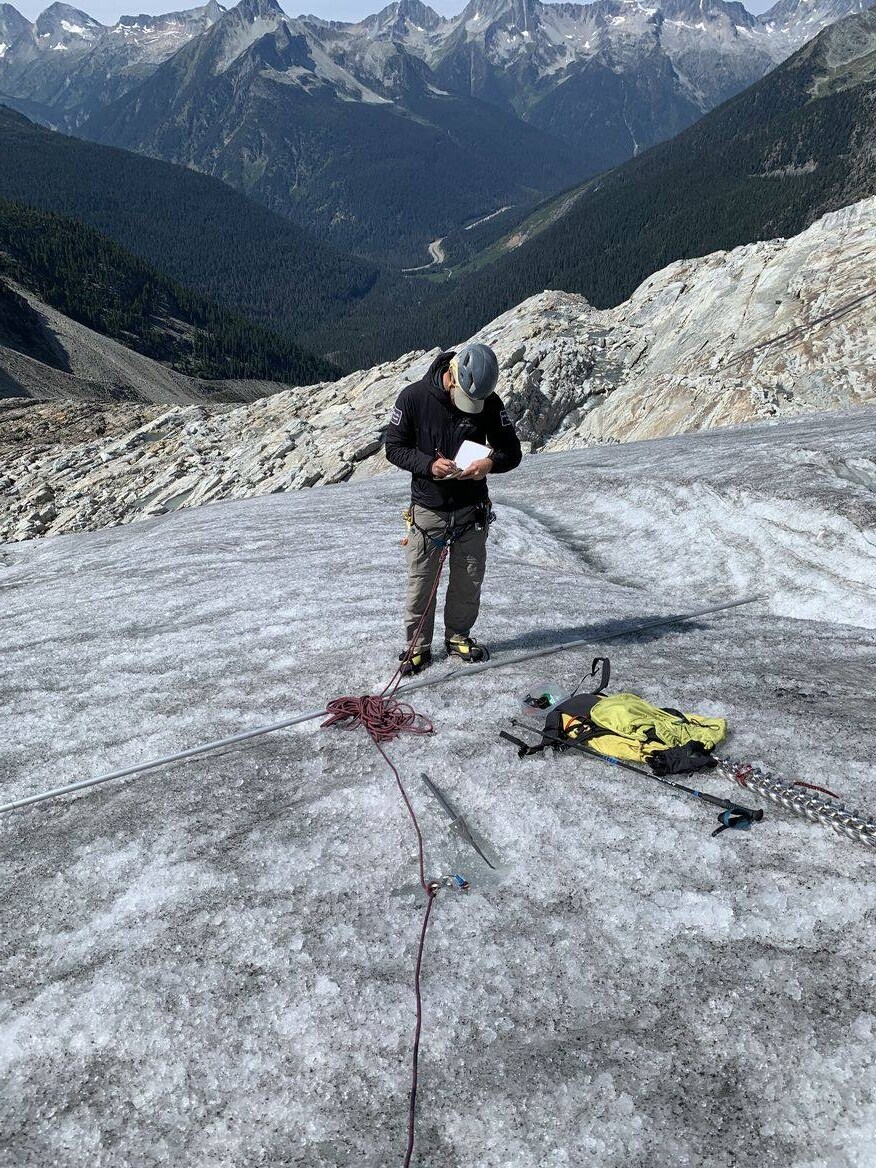

In Mount Revelstoke and Glacier National Parks, a small team of researchers are monitoring the Illecillewaet Glacier by visiting it three times a year. In spring, they measure how much snow has built up over the winter. In summer, they check and maintain their equipment. In fall, they measure how much ice and snow has melted during the warmer months. This helps them calculate the glacier’s mass balance, which is the difference between how much snow and ice a glacier gains and how much it loses over time. A positive mass balance means the glacier is growing; a negative one means it’s shrinking. To gather this data, scientists dig into the snow and ice to collect samples and use long stakes drilled into the glacier to track surface melt. Back at the office, they enter the data into a spreadsheet to calculate how the glacier is changing year by year.

What type of education/training/certification is required to work with the Glacier Fieldwork Team?

Glacier fieldwork is undertaken by a small group of 2-4 Parks Canada staff. While there aren’t specific education criteria for this role, all staff doing backcountry fieldwork need to have the appropriate training, such as snow and ice travel experience. For this specific fieldwork, each team member needs to be trained in glacier travel, crevasse rescue, and at least one team member needs to have the appropriate level of first aid for the work activities. In most cases, the Resource Conservation staff who support this type of monitoring have a Bachelor of Science degree in natural resources or similar field. The coordinator also needs significant fieldwork experience, which may be obtained through mentorship opportunities with subject matter experts, such as glaciologists. Working as a glacier fieldwork assistant is an excellent opportunity to learn about the methods used to measure glacier mass balance and to gain the experience needed to conduct independent fieldwork in the future.

Why are measuring and tracking glacial meltwater, surface glacier mass balance, and glacier volume so important? What do these readings inculcate about the “health” of a glacier?

Glacial meltwater, surface glacier mass balance, and glacier volumes are all reliable annual indicators of how snowfall, rainfall, and temperatures are affecting the overall health of a glacier. Glaciers provide many important benefits to people and ecosystems located downstream. During extended summer droughts, a large proportion of the water found in streams comes from glacial melt, which can be used for drinking, agriculture, industries, and electricity production. Glacial meltwater also keeps stream temperatures cool, which is vital for many freshwater species, like the threatened Pacific Bull Trout and Westslope Cutthroat Trout, that rely on lower temperatures to survive. When a glacier has a positive mass balance (meaning it gains more snow and ice in winter than it loses in summer) it can provide a steady flow of water to downstream environments each year. Measuring a positive mass balance means the glacier is growing in volume; however, this is not what we are seeing from glaciers in Glacier National Park. Most glaciers in the park are shrinking. They are getting thinner, their edges are receding at record speeds, and they’re contributing less water to rivers and streams downstream.

How many glaciers are in Glacier and Mount Revelstoke National Parks?

Parks Canada counts glaciers using aerial imagery and remote sensing data. It is difficult to say definitively how many glaciers are in Mount Revelstoke and Glacier National Parks. The total depends on how small a glacier can be and still be considered a separate glacier. In Glacier National Park, glacial recession is being observed in real-time. In 2018, there were 129 glaciers in the park, down from 337 in 1978, which represents a 60% loss in only a 40-year span. Mount Revelstoke had 19 glaciers in 1980 and 17 in 2011. It’s often easier to look at the total surface area of glaciers rather than count how many there are. As glaciers melt, they can break apart into multiple smaller glaciers, which makes it harder to track them by number alone. Therefore, as big glaciers shrink, the number of glaciers in each area may actually increase, even though there is overall less glacial surface area. In Glacier National Park, the glaciated surface area has declined by 36.6% between 1978 and 2011. In Mount Revelstoke National Park, between 1980 and 2011, the glaciated surface area has declined by 38.8%.

In your opinion, what is the biggest threat to glaciers in the Selkirk and Purcell ranges?

Seasonal observations at Glacier National Park tell us that changing climate conditions are contributing to the shrinking of glaciers in the Selkirk and Purcell ranges. Warmer summers, less snowfall in winter, and more rain instead of snow are all contributing to their decline. Wildfires also play a role; smoke and ash can settle on glacier surfaces, making them darker and causing them to absorb more heat, which speeds up melting.

What is the best part of your job?

I am lucky enough to visit the Illecillewaet Glacier multiple times per year and learn about the complex nature of this ecosystem firsthand. I’ve seen the glacier change over time, witnessed its edges recede, rocky outcrops grow taller and larger as the surrounding ice thins, and new crevasses open on the upper glacier. Though glaciers are inherently dynamic landscapes, we have seen climate change accelerate these shifts, especially with the record high temperatures we’ve experienced in the last few years.

What is one of the most challenging aspects of your job?

Coordinating field visits is one of the most challenging aspects of glacier monitoring. Each visit requires a minimum of three team members who have the required training and experience to safely travel on glaciers and carry out the monitoring work. Depending on the season and the travel conditions, at least one of the team members must be a certified ski guide or mountain guide. Often this work requires the use of a helicopter. Both the helicopter and qualified staff must be available on a day with clear visibility, little or no precipitation, and no thunderstorms. These conditions ensure the helicopter can fly safely to the upper glacier, located just below 3,000m in elevation. There are a lot of variables to consider!

Glaciers are inherently dangerous places, so how do you mitigate risk while working on the ice?

Working safely on glaciers takes careful planning and preparation. We choose weather windows with clear skies so we can see and assess hazards like crevasses. Everyone on the team has training and experience in glacier travel and crevasse rescue. Depending on the season and conditions, we’re always accompanied by a certified ski or mountain guide. We carry the right gear, including helmets, ropes, crampons, ice axes, and rescue equipment and often travel roped together for safety. When working on steep ice, we anchor ourselves with ice screws. In winter, we also bring avalanche safety gear. To stay connected, we do regular radio check-ins and we also carry first aid kits. And if conditions change suddenly, we always have the option to call a helicopter for a quick exit.

Any final thoughts?

As glaciers in Mount Revelstoke and Glacier National Parks recede, it is important to understand how the loss of glaciers could affect local wildlife, water supplies across the region and country, and even tourism. Climate change impacts to Parks Canada-administered places are complex and outside of our control, and Parks Canada is committed to taking action by integrating climate change mitigation and adaptation actions into its work, including decarbonizing energy use and exploring options for increased public transportation in park operations. Glaciers have characterized our mountain landscapes for millennia and are vital to alpine ecosystems for nutrient cycling, water distribution, and habitat sustainability.

I would like to take this opportunity to thank Michel for the detailed responses to my questions. Your expertise and insight have allowed us a glimpse into the important work being done in, on, and around glaciers in the mountain national parks. Thank you for your time, your honesty, and your valuable contributions to climate science.

For even more glacier-related stories, please see Wild Jobs: Glacier Guide, Historic Photos of Glaciers from the Canadian Rockies, Old Photos of Glaciers from Western Canada: Part 2, and Touch Ice, Take Action with Glacier Hikes and Adventures. You can also learn more about a couple more of Parks Canada jobs, including Park Wardens and the Warden Service Dog Handler by following those links.

***

About this column:

Wild Jobs is a running series that focuses on people in outdoor-related professions. It provides a brief snapshot of their career and the duties that it entails. Please see my latest instalment, Wild Jobs: Director of the Canadian Ice Core Lab, to learn more.