As Calgary residents we are fortunate to have Banff National Park in our own backyard. I’m willing to bet if you’re reading this that you’ve spent some time within Banff’s borders, but do you truly know the history of how the park was formed? Each year Banff welcomes between three and four million visitors, many of whom are blissfully unaware of the park’s colourful history, which makes visiting the Cave and Basin National Historic Site all the more important.

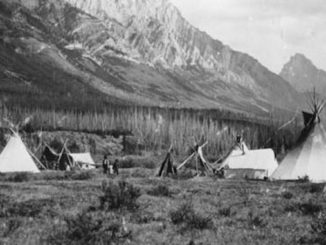

Modern carbon dating techniques have calculated that the first human activity in the Banff area was over 10,000 years ago. Pre-contact First Nation people used the area to hunt bison and other wild game. Much later, in 1875, construction on the transcontinental railroad began, which would link Canada’s west coast with the rest of the country. In the fall of 1883, a few years prior to the completion of the railroad, William McCardell, his brother Tom, and their partner Frank McCabe, three Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) employees, were the first European’s to “discover” the cave and basin on the lower slopes of Sulphur Mountain. Considering First Nation stories exist about the cave’s warm waters and human activity was present long before Europeans arrived, we know that these three CPR workers were not the first to actually discover the thermal springs. They were, however, the first to realize the potential profit flowing in the warm mineral water. They erected a fence and built a cabin near the cave’s entrance, staking their claim; unknowingly creating the crude boundaries of Canada’s first national park.

“…like some fantastic dream from a tale of the Arabian Nights”

-William McCardell describing the mist-filled cave they discovered

The three CPR employees laid claim to the site by writing to the Government of Canada, but the government, also recognizing the monetary potential of the medicinal waters and needing to raise funds to complete the railroad, denied their claim. The dispute turned into a legal battle over rightful ownership. Eventually the dispute was solved when the government created the 26 square-kilometre Hot Springs Reserve in 1885. Two years later, in 1887, the Hot Springs Reserve was expanded to include 665 square-kilometres of wilderness and became officially known as Rocky Mountains National Park; the first of its kind in Canada. Through the National Parks Act, Rocky Mountain National Park was renamed Banff National Park in 1930 and became Canada’s flagship park. It wasn’t until 1981 that the Cave and Basin was designated a National Historic Site.

The Cave and Basin underwent a major, three-year, multi-million dollar renovation project and just reopened to the public in the spring of 2013. In addition to the cave the site also features a welcome centre, an interactive information centre, the outdoor thermal basin, and over ten kilometres of interpretive trails. There’s also the new Enemy Aliens: Prisoner’s of War exhibit that was constructed during renovations. For additional information about the POW exhibit please refer to my previous post titled, Lest We Forget.

The Cave and Basin is also home to Banff National Park’s most at-risk species, the Banff Springs Snail. This snail is only found in a handful of thermal springs within the park and nowhere else on Earth. Much like Grizzly Bears are used to indicate the health of large ecosystems, this snail is an indicator species for the much smaller, but very unique, thermal spring ecosystem. Snail numbers increase and decrease with seasonal rise and fall of water temperatures. Their numbers are also greatly affected by vandalism and exposure by humans in their aquatic environments. Of the nine thermal pools on the slopes of Sulphur Mountain, the snails are now only living in seven. These pools are the only place in the world where the snails live, and as such, are highly regulated by Parks Canada.

The next time you find yourself in Banff delve into a piece of Canadian history with a visit to the Cave and Basin National Historic Site. I’ve been there on two separate occasions (before and after the renovations) and I seem to learn something new each time I go. I have also gained new appreciation for the site, because without it Banff National Park might not exist and that would be a disservice to all Canadians.

“The parks are hereby dedicated to the people of Canada for their benefit, education, and enjoyment…and such parks shall be maintained and made use of so as to remain unimpaired for future generations.”

-Natonal Parks Act, 1930