“mahzahkahzah

remembers asking for directions

to indian paintings

on a wall up the high canyon of grotto”

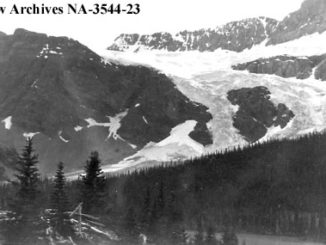

The Bow Valley has been inhabited for thousands of years; long before the first Europeans arrived in the mid-to-late 1700’s. The name ‘Bow’ refers to the bow reeds that grow along the river’s edge, which are similar to Saskatoon bushes. The Stonies called the river Manachaban, ‘the river where the bow reeds grow’. This is a reference to Saskatoon saplings being used to create bows for hunting game. These early First Nation groups left their mark on the land in a number of ways, one of which can still be viewed today. In three separate locations those with a keen eye are able to uncover pictographs, or rock paintings, that are believed to be anywhere from 500 to 1,500 years old.

Pictographs and petroglyphs are types of prehistoric artwork that are common across the country. Petroglyphs are rock carvings that are created by removing part of a rock’s surface through a variety of techniques, such as scraping, scratching, or pecking. Pictographs, on the other hand, are paintings that were created using a mixture of naturally occurring iron-based minerals, commonly referred to as ochre, and an organic binding agent, such as animal fat, water, blood, or even urine. When combined, the mixture becomes a liquefied paste that can then be applied to the surface of rocks. It is believed that rock art is Canada’s oldest and most prevalent artistic tradition even though accurately dating many sites has proven difficult. Much of the artwork across the western provinces can be linked to shamanism, vision quests, or the search for helping spirits.

Accurately revealing the meaning behind such artwork or establishing who is truly responsible for their creation are questions that have plagued archaeologists, historians, and amateur explorers alike. Grassi Lakes, Grotto Canyon, and the entrance to Rat’s Nest Cave all contain collections of fading pictographs; painted using red ochre, the most common pigment in this part of the country. If you’ve ever had the privilege of visiting these sacred sites you’re sure to recognize the deteriorated state of many. Time, weather, vandalism, or some combination thereof, are causing these culturally important sites to slowly disappear. With the help of a digital enhancement technique known as decorrelation stretch, or DStretch, archaeologists are able to enhance photographs for better interpretation, understanding, and preservation.

At the end of a picturesque hike sit two majestic turquoise bodies of water known as Grassi Lakes. Past the lakes and just off the trail a sign indicates the location of the pictographs. This site contains several paintings, but the most well-preserved is that of a human character holding a large ring. It is believed this image represents a Medicine Man, a prominent figure in many First Nation cultures. Medicine Men are largely considered to be healers, seers, and philosophers within their own tribes.

Rat’s Nest Cave sits on the slopes of Grotto Mountain and is the least accessible of the three sites. The cave is located on private land and access is restricted unless accompanied by a guide. The exterior entrance to the cave was once adorned with pictographs, namely painted handprints, but these have all but vanished with time and weather. Inside the cave’s main entrance is a lone pictograph depicting another Medicine Man, although it too is slowly disappearing. Much like the figure at Grassi Lakes, this human-like image appears to be holding a large ring.

“mahzahkahzah

remembers reaching the place

where two canyons

meet the riverbed

gouged through sedimentary stone

remembers burnished walls rising

above him when one

of the women cries

‘there they are!’”

Nearby is the very popular day-trip of Grotto Canyon. Here the smooth canyon walls contain the largest collection of artwork within the Bow Valley. The paintings here contain human beings, animals, and anthropomorphic figures. Although there isn’t a Medicine Man depicted at this site there is one unique painting of a fluteplayer, sometimes referred to as Kokopelli. The pictographs in Grotto Canyon may appear glossy or waxy. This is due to the slow build-up of calcite on the canyon walls, which is slowly covering the paintings.

“he then silently

unrolling large sheets of tracing paper…

… remembers placing

a sheet over smooth stone

where rain and wind have worn the three

hunters and a bison

into a soft stain

pigment”

The creators of the aforementioned artwork are the source of much controversy, but most will agree that all three sites are collectively linked. The most popular theory is that the Hopituh Shi-numu people, or Hopi for short, are responsible for all of the artwork found in the Bow Valley. According to legend, the Hopi sent off members of their tribe in the four cardinal directions with the intention of meeting again at a common place, which ended up being present-day Arizona. Much of the Bow Valley artwork is remarkably similar to paintings found throughout the southwest United States. The fluteplayer is also a traditional symbol of the Hopi people and in their culture Kokopelli is a hunchbacked trickster who acts as a symbol of fertility and as a rain priest.

Conversely, the Stoney people, many of whom reside on the Stoney Nation close to the Bow Valley, have their own interpretations about how the pictographs were created. One story describes members of the Stoney tribe returning from the south with Hopi captives, who subsequently left their mark in the valley. An alternative explanation is that the Stoney people inherited the spirits of their Hopi captives, which granted them the ability to create similar imagery. Another story concludes the paintings were actually created by the Stoney people after returning from a southern journey and observing foreign artwork.

It’s evident the true meaning of these revered sites has been lost through the passage of time. There will be continued speculation and conjecture mixed with controversy, but the fact remains many questions will forever be left unanswered. Whatever the reason for their creation, the Bow Valley and its present inhabitants are richer by knowing this was a place of great significance for its earliest occupants. Regardless of who may have painted them, the artwork in the Bow Valley shows a deep connection with the land that is still very much apparent for us today. The Bow Valley and its mysterious pictographs have many stories still to be told.

“remembers giving up

to take another sheet

begin again

wary of overdrawing

the hunter and spear

for fear of distorting

retraced self

remembers wondering

about those three hunters

the way they stand

with tomahawk arrows

sword or staff

and medicine man’s rattle

like wisemen’s gifts

to be given away

if the chief’s newborn

son lives”

~Tracing a poem by Andrew Suknaski, 1970

This is my second story featuring First Nation rock art. Please visit my previous post titled, Hunting History for additional information about rock art sites in southern Alberta. You can also visit this blog post for further details, information, and photographs.