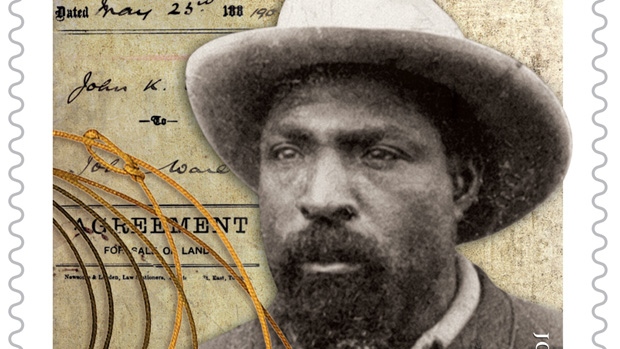

When discussing history it can be challenging to discern fact from fiction; truth from tale. Detailed record keeping was not what it is today and many stories were only passed on orally; their words never gracing a page. These imprecise accounts routinely inflate the accomplishments of many historical figures, but like any good yarn most are rooted in some version of the truth. Many Canadians have left lasting legacies due to their larger than life reputations (Wild Bill Peyto comes to mind), but nobody in Alberta’s rich ranching history has reached the same legendary status as the man known as John Ware.

John was born into slavery in 1845 on a cotton plantation in South Carolina. In 1865, at the end of the American Civil War, John became a free man. He headed west to Texas where he found work on a ranch. It was here that he honed his skills in ranching and horsemanship; two areas that have greatly attributed to his near-mythical status in Canadian history. In 1882 John was hired as part of a group to drive 3,000 head of cattle north across the border to the recently established Bar U Ranch (now a National Historic Site). John never returned to the United States, opting to stay in Canada where he worked on different ranches, further polishing his already exceptional skills with horses and livestock.

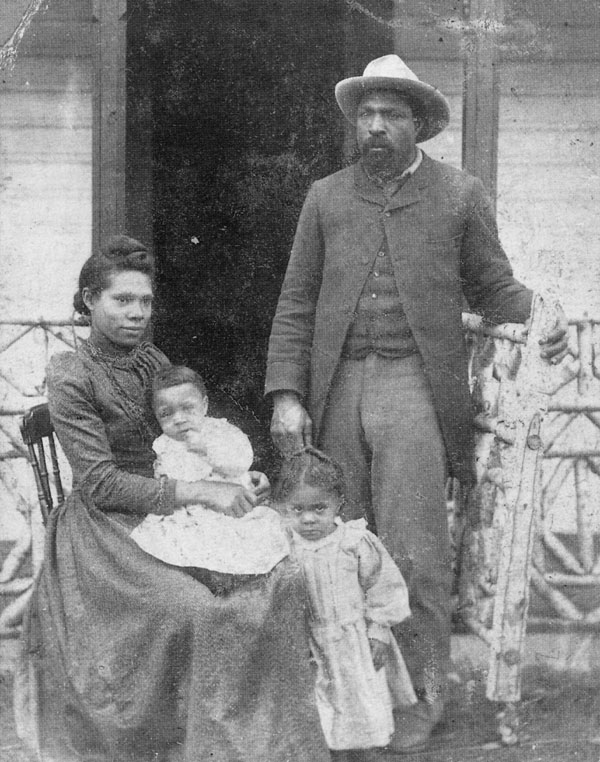

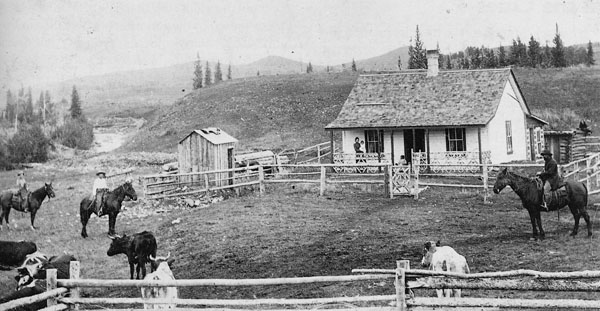

By 1890 John had established his own ranch and registered his own brand as the four nines (9999), also known as the walking stick brand. In 1892 he married Mildred Lewis, a transplant from Ontario, and together they had five children (sadly a sixth died in infancy). In 1900 the family relocated their ranch to the banks of the Red Deer River, somewhere downstream from the city of Brooks. Flooding in 1902 destroyed their original cabin but John rebuilt it, albeit on higher ground overlooking a small stream, which is now known as Ware Creek. Then in 1905 tragedy struck the family. In April of that year Mildred died of pneumonia and typhoid and just five months later John was killed in a freak accident when his horse tripped in a hole and fell, landing on him. John’s death occurred a mere twelve days after Alberta became Canada’s tenth province. His funeral, held in Calgary, was the largest ever in the city’s young thirty-year history. After the funeral the Ware children were sent to live with their grandparents and the land was later sold.

In the years succeeding his death, the John Ware Cabin deteriorated and fell into various stages of disrepair. With the help of volunteers and organizations such as the Brooks Kinsmen Club, the Dinosaur Natural History Association, Alberta Environment Protection, Alberta Historical Resources, and Old Bones Productions the cabin was restored in the late 1950’s and again in 1993. In 1998 Parks Canada was chosen to fully restore the cabin based on their extensive knowledge of preserving historical log structures. The cabin was officially unveiled during Parks Day festivities in July of 2002 and to this day remains a major attraction in Dinosaur Provincial Park.

“Not only one of the best natured and most obliging fellows in the country, but he is one of the shrewdest cow men, and the man is considered pretty lucky who has him to look after his interest. The horse is not running on the prairie which John cannot ride.”

~ quote published in 1885 in the Macloed Gazette

Stories about John always seem to include two central elements; his tremendous strength and natural skill with both horse and cow. Witnesses claimed that he could walk across the backs of penned cattle without fear or that he could stop a steer head-on and wrestle it to the ground; possibly giving truth to the legend that he invented steer wrestling long before it became a popular event at rodeos. It’s also been said that he could break the wildest broncos, easily lift an eighteen-month-old steer onto his back for branding purposes, and hold a horse on its back by hand in order for it to be shod. There was also the time that his team of horses died in an unexpected storm and John had to pull the wagon and its passengers back to the ranch by himself; his only complaint was that he’d need to break-in a new team. His enormous appetite was almost as legendary as the man himself. Cooks claimed to have fed him on oversized platters while others say that he ate sandwiches the size of the Holy Bible. There’s even a tale that John discovered the Turner Valley oil fields with just the flick of a match! Whether you believe the stories or chalk it up to nothing more than folk tales one thing is obvious, the man’s exploits have earned him a reputation like no other. There is one story, however, that is allegedly all true; the time he used a Calgary bridge as a cattle crossing. When he moved his family from the Millarville area to the Red Deer River the city of Calgary proved to be a major obstacle in his path. Driving the cows through the city was impractical and possibly illegal, but that didn’t seem to stop him. Instead of going around John drove his cows to the edge of the Bow River and waited for nightfall. After dark he herded his cows across the river using Calgary’s bridge, all while riding himself into the history books. He was the last, and quite possibly the only rancher to use a city bridge as a cattle crossing.

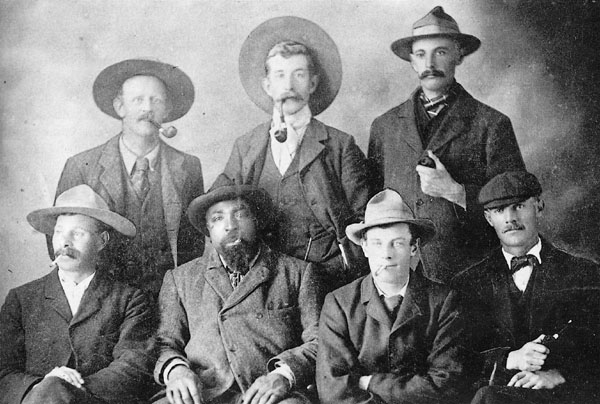

In a time when racism was rampant, John Ware managed to earn the respect of his peers through hard work, skill, honesty, and courage in the face of adversity. First Nation groups referred to him as Matoxy Sex Apee Quin (bad black white man), due to his mettle and strength. By all accounts it would seem that John was well-liked by everyone he encountered. His folk-hero status, attained in a time that was dominated by white males, is further proof of the level of respect and admiration he garnered throughout his extraordinary life. After death the man’s legacy has lived on in a variety of ways. In southern Alberta Mount Ware, John Ware Ridge, and the previously mentioned Ware Creek all carry his moniker while the city of Calgary has John Ware School and the John Ware Building on the SAIT (Southern Alberta Institute of Technology) campus features the 4 Nines Dining Centre.

I think these words from an unknown source sum up the legendary figure of John Ware perfectly, “Cowboy is a breed tougher than nails and stronger than steel.”