Our story begins 10,000 years ago at the end of the last ice age. As glaciers and ice sheets melted they retreated, carving the landscape and leaving the Canadian Rockies in their current rugged form. Left behind were depressions in the ground that eventually filled with meltwater creating glacial lakes and tarns. Over time some of these water bodies were naturally inhabited by native species of fish. Others remained empty, usually due to a natural barrier such as a waterfall, preventing fish from traveling further upstream.

When it comes to historic years, 1885 was a big one for an eighteen-year-old country known as Canada. The Hot Springs Reserve (that would later become Banff National Park) was established and the Canadian Pacific Railway was completed. Once the tracks were laid the country was connected from east to west and railroad companies were competing for travellers (and their money) to use their specific railway lines. The Canadian west was touted as pristine and ripe for exploration. Rugged wilderness filled with unclimbed peaks, plentiful big game, and waterways bursting with fish were some of the promises used to lure tourists out west. Similar tactics continued for decades. In an effort to enhance the finishing experience for visitors, Parks Canada, the governing body for Canada’s national park system, began introducing non-native fish species into the mountain national parks. The practice of introducing non-native fish, such as Brook Trout, started in the 1940s and continued for nearly 40 years.

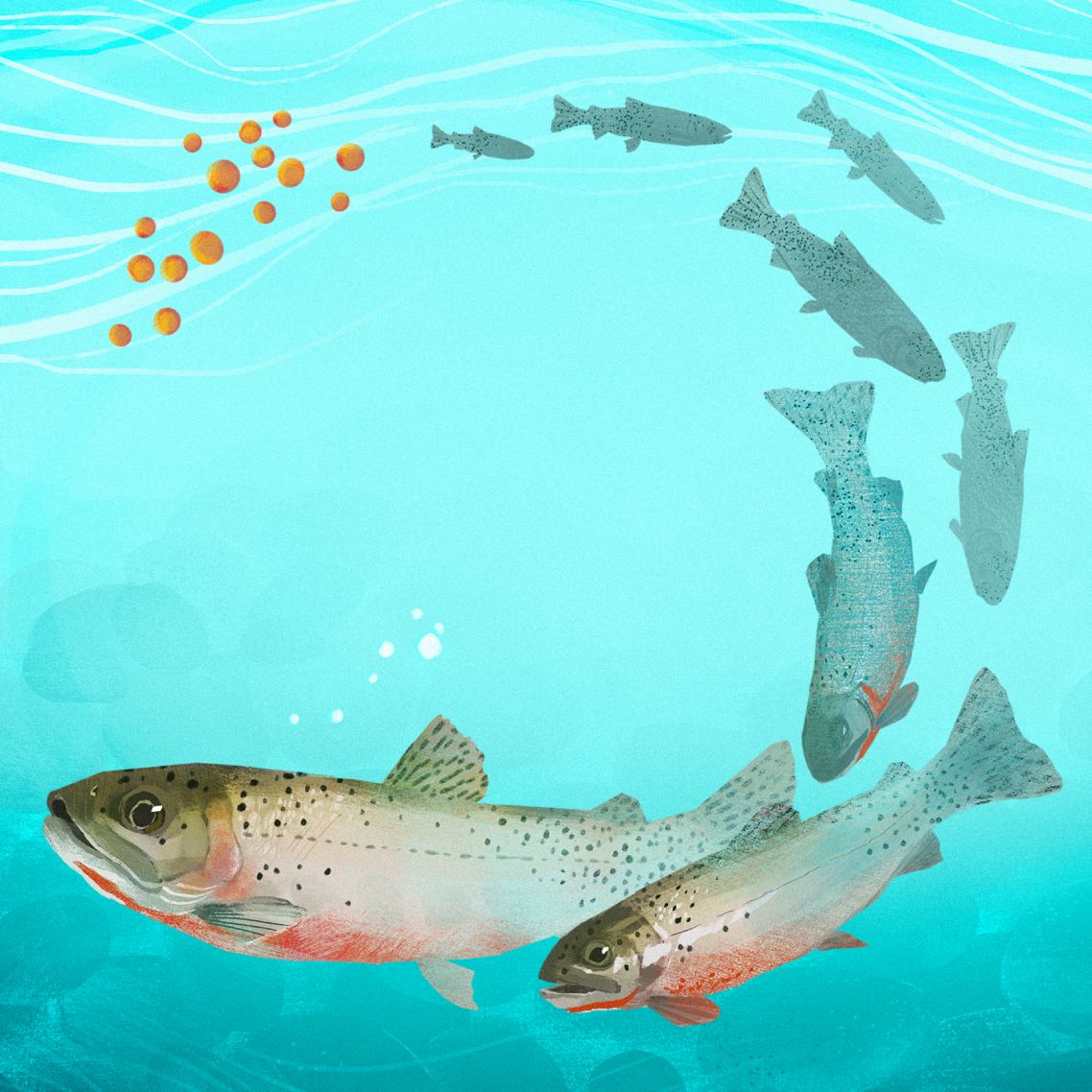

Since that time the science has improved and we now know that introduced species can have devastating effects on an ecosystem. Westslope Cutthroat Trout are native to Banff National Park and are considered an indicator species. Their presence in an environment shows that an ecosystem is healthy. Unfortunately, Banff’s Westslope Cutthroat Trout are at risk of extinction. Introduced species are out-competing them for resources. The Westslope Cutthroat Trout gene pool is also being diluted through hybridization. They are inter-breeding with introduced species, such as Rainbow Trout and Yellowstone Cutthroat Trout, creating hybrid species.

Westslope Cutthroat Trout play an important role in their ecosystem. Shelley Humphries, an Aquatic Specialist with Parks Canada, says, “The time of year and location that Westslope Cutthroat Trout spawn is ecologically important. They are food for bears when they come out of hibernation and for ospreys that have migrated here. Their eggs are also accessible to Harlequin Ducks when they need food to produce their own eggs.” Brook Trout, for example, spawn in autumn, a less important time of year for the ecosystem. Their eggs are deposited deep in the gravel beds, making them inaccessible to those further up the food chain. In these ways, non-native fish cannot replace the importance of Westslope Cutthroat Trout.

Climate change is warming our waterways, habitats are being degraded and less connected, turbidity is increasing due to erosion and urban runoff, and non-native species are out-competing native fish populations. Westslope Cutthroat Trout need cold, clean, complex, clear, and connected waterways to survive. All of the aforementioned factors help explain why genetically pure Westslope Cutthroat Trout are found in less than ten percent of their historic distribution in Alberta and are now only in a handful of places in Banff National Park.

Parks Canada plays a critical role in recovery efforts for species at risk. They work with provincial and federal agencies, and other key stakeholders, in an effort to restore native trout populations. With regards to Westslope Cutthroat Trout, Parks Canada devised a four-part plan to guide restoration efforts. First, quality habitat needed to be identified. Hidden Lake was ideal as the area provides a natural refuge, a waterfall, preventing other non-native species from entering.

The second step involved removing all non-native fish from Hidden Lake. Over a six-year period, Parks Canada staff used netting, electrofishing, and angling practices to eliminate non-native species, but they continued to thrive. After extensive consultation with fisheries experts from Canada and Montana, Parks Canada opted to use a naturally-occurring chemical called Rotenone to remove any remaining fish. Rotenone is a fish toxicant made from the roots of bean plants that has been proven safe to use without negative effects on the surrounding ecosystem or other species of birds, mammals, or people.

Once the non-native fish were removed, Parks Canada began reintroducing genetically pure Westslope Cutthroat Trout to the Hidden Lake basin. The team opted to use the stream-side incubation technique to reintroduce the fish. The Allison Brood Trout Station in southern Alberta was originally responsible for looking after the eggs for the first twenty days before the Parks Canada team placed them inside artificially-created eggs nests that were located inside of buckets. The buckets were partially submerged in the stream, allowing the eggs to be immersed in the same water they’ll spend the rest of their lives in. In an effort to minimize egg transport and handling time, and keep costs lower, Parks Canada developed their own incubator. This also allowed the aquatics team to raise trout entirely within Banff National Park. The team placed thousands of eggs into the Hidden Lake basin with the goal to have fish old enough to spawn every year. 2024 was the final year that Westslope Cutthroat Trout eggs were introduced to Hidden Lake.

The final step is monitoring for success. The Parks Canada team successfully restored Hidden Lake and approximately four-kilometres of stream. The aquatics team is also utilizing environmental DNA (eDNA) to monitor the restoration work and any possible effects of Rotenone on the ecosystem. They are happy to report that no negative effects have been discovered.

Although their efforts at Hidden Lake have been successful, the journey is not over. Conservation and restoration efforts are still underway and will continue into the future. But thanks to the dedicated work of Parks Canada, Westslope Cutthroat Trout are swimming in Hidden Creek for the first time in 50 years!

For several years Parks Canada offered guided hikes to the Hidden Lake basin. I was given the opportunity in September to visit Hidden Lake with one of these tours. While Hidden Lake is open to anyone, traveling with a guide was a wonderful experience and allowed me to better understand the important conservation work being done there. Parks Canada decided to discontinue the Hidden Lake guided hike at the end of the 2024 season. It is unclear at this time whether future conservation-based hikes will be offered in the future. Parks Canada still offers guided hikes to the Burgess Shale and Mt. Stephen in Yoho National Park and to Stanley Glacier in Kootenay National Park.

For additional information about Westslope Cutthroat Trout and the conservation efforts to save them please refer to the following, Saving Cold Water Loving Fish in Mountain National Parks, Westslope Cutthroat Trout, and Alberta Native Trout. You can also watch the video clip below.