Deep beneath Canada’s frozen landscape, a hidden archive of Earth’s climate history is being unlocked, one core at a time. Ice core drilling, the process of extracting cylindrical samples of ancient ice from glaciers and ice sheets, is a powerful scientific tool that allows researchers to look back in time, sometimes hundreds of thousands of years. Each layer of ice captures tiny bubbles of atmosphere, dust, and volcanic ash, offering a year-by-year record of past climates. In Canada, this research is especially vital as our northern ice caps, like those in the Canadian Arctic and the Columbia Icefield, hold essential clues to the planet’s shifting climate.

At the heart of this research is the Canadian Ice Core Lab (CICL), located at the University of Alberta. This state-of-the-art cold lab is home to Canada’s only national ice core facility and stores ice collected from Canadian and international expeditions. Maintained at -35°C, the lab provides researchers a place to carefully analyze ice cores using advanced techniques to measure greenhouse gases, trace elements, and isotopic compositions. These details help scientists reconstruct temperature fluctuations, atmospheric chemistry, and pollution levels from the past – and understand how today’s climate crisis compares.

The findings from Canada’s ice cores are helping answer urgent global questions. Data gathered here contributes to international climate models, helping policymakers anticipate future changes in water resources, sea level rise, and extreme weather events. They also provide crucial context for Indigenous communities and northern regions already experiencing rapid environmental shifts. As Canada faces accelerating glacier loss, ice core science is not only a window into Earth’s climate past, it’s a call to action for its future.

To learn more about CICL and the work being done there, I reached out to Alison Criscitiello, the lab’s Director, who just returned from the field where she was drilling new ice cores in Canada’s High Arctic. In addition to her day job, Criscitiello is also a leading high-altitude mountaineer and a Royal Canadian Geographical Society Fellow.

Why do you drill ice cores in the first place?

Well, the general reason we drill ice cores is to be able to reconstruct past climates. That doesn’t just mean temperatures of the past, but all sorts of different parts of the past environment, which can include understanding wildfire history or sea ice variability or greenhouse gases. We do all of that with the intent of learning about natural climate variability over a long time scale to better predict future change. And, of course, some of that now involves the additional story that’s been etched on natural climate variability; the human-imprinted piece of it all.

So you’re saying there are trapped bits of old atmosphere within the ice?

Yes! There are two components of what has been preserved within the ice. One is the liquid chemistry of the ice – what made up the snow that fell that day. And then there’s also the gasses trapped within the ice. Once you reach a deep enough depth and a high enough pressure, the little air spaces within the ice get trapped. They become closed off from one another, so you get trapped bubbles of ancient atmosphere. We can look at both the liquid chemistry of the ice and at the chemistry of the gases trapped within the ice.

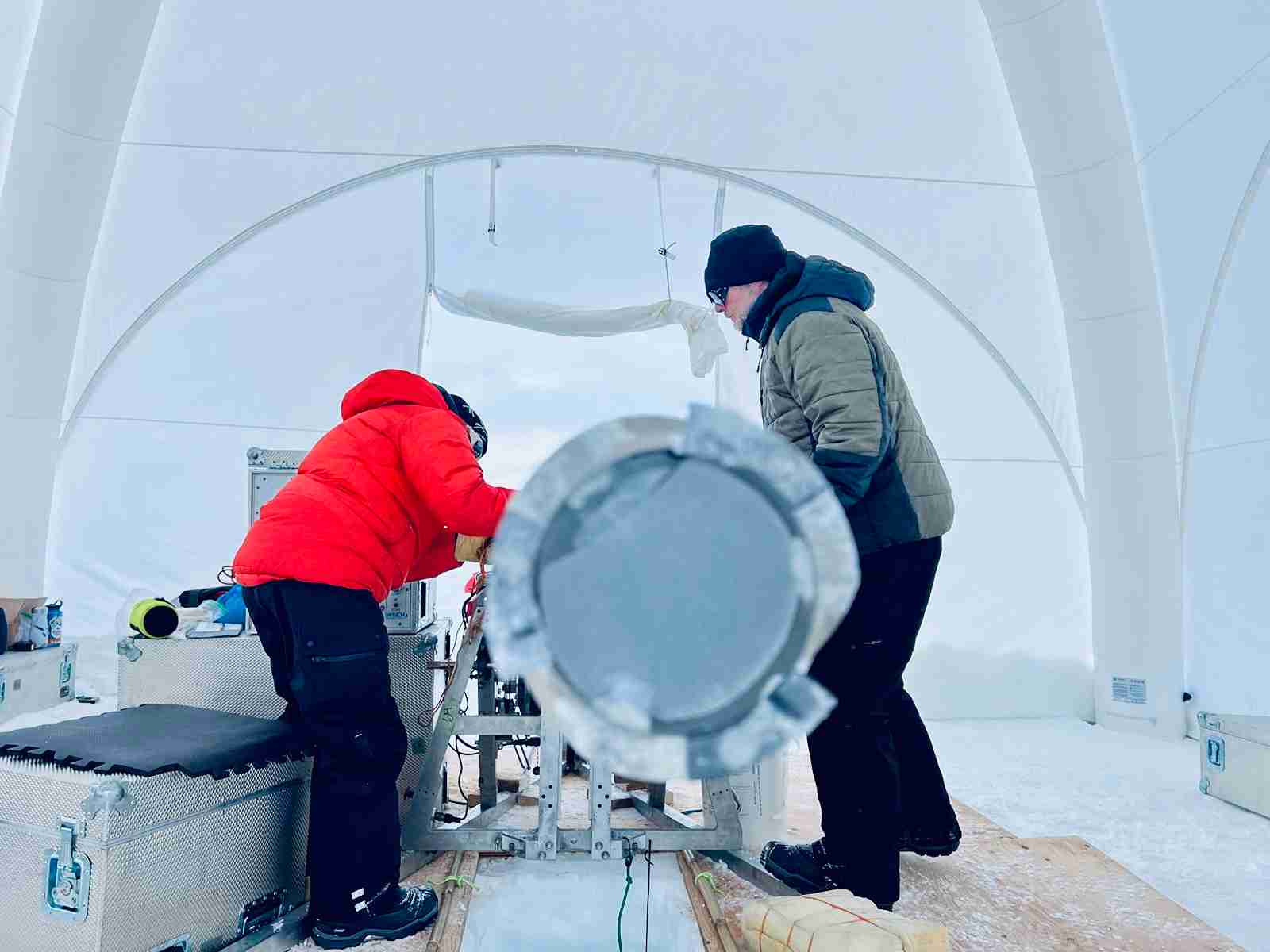

You mentioned that you just returned from drilling a really deep ice core, something that would typically take two field seasons but you were able to complete it in just one. How were you able to do that?

The way we could make that happen was we went in early, before a typical Canadian High Arctic field season would start (before April), when it was still incredibly cold. That is usually not the kind of temperature we like to drill in. We also pushed it on the other end, staying until temperatures were a bit warm for ice core drilling (late May). We pushed the extremes on both sides, but it worked out. We drilled to a depth of 613 metres, which is the deepest ice core ever drilled in all of the Americas.

Who has access to the Ice Core Lab, and what kind of research are they doing?

Good question! Anyone can use the lab. It’s technically a national lab, so truly anyone has access to it, and lots of different people do use it, both from within Canada and internationally. It might be students, other scientists, or even artists. I actually started a visiting artist program a couple of years ago, so all sorts of people come. Most people, though, are coming to access the archived ice that we have stored here. We have about three kilometres of ice in the lab right now. You can see our ice inventory online, so lots of times people will see what he have and then determine what they’d like to do with it.

Is this the only lab of its kind in Canada?

Yes, it is!

What’s the strategy behind where you are drilling? Are you trying to get samples from as many different locations as possible?

That’s a really hard question to answer, and my answer even a few years ago would be different than now. What drives a lot of the decision-making around priority locations to drill has to do with where it’s warming the fastest and where those climate records are being lost. So, where we just were, despite it being 80-degrees North, it is one of those places that’s melting rapidly in summer. So is the Columbia Icefield here in Alberta. But of course there are other big international ice core projects going on in places like Antarctica that have nothing to do with that kind of urgency. They’re simply looking at different scientific questions.

What would you say is the best thing about your job?

I love the field work! The field work and the people. I spend a lot of the time in the field, and I really, really love it. I do this kind of science because I love the frozen places of our planet.

What’s one of the most challenging aspects of your career?

The funding! I mean, altitude and cold are big things I contend with a lot of my year as well. So, funding, altitude, and cold, in that order.

Your career has taken you to some of the most remote, inhospitable places on the planet. Do you have a favourite?

It’s hard to weigh places against each other, but I think the island I was just on, Axel Heiberg Island, in the Canadian High Arctic, might be my favourite. It has these incredible mountains along the coast, and it was teeming with Arctic Wolves. Usually, my work takes me to the highest, most inland parts of ice caps, and there’s just nothing there, so I rarely see wildlife. It’s always just flat, white nothingness. But there, it was a small enough ice cap that I could ski to the edge and see this enormous mountain range with all this life. It’s just richer.

Once your field season wraps, what does the rest of the year look like for you?

Now I get to spend more time in the lab. The ice is already here. For a core of this length, we’ll spend five or six weeks in the -25°C lab cutting and imaging the ice. Then we’ll spend a few months doing the chemistry and analyses on the ice, then data analysis and writing papers, and discovering what stories were in that core. Then we get to do it all over again, so it’s kind of a cyclical job, which I really like.

Ice core drilling is more than a method; it’s a gateway into Earth’s environmental memory. Each extracted core offers a layered story of ancient atmospheres, shifting climates, and the far-reaching fingerprints of human activity. In Canada, this work is helping scientists decode the unique climate history of the Arctic and alpine regions, while labs like the Canadian Ice Core Lab are transforming these frozen records into meaningful data that shape our understanding of the past and inform future climate strategies. As ice continues to vanish from mountaintops and polar landscapes, the urgency to preserve and study these archives grows. The next frontier lies in deeper drilling, finer analysis, and broader collaboration, so we can better predict, adapt to, and perhaps even mitigate the accelerating changes unfolding across our planet.

I would like to say a special thank you to Alison for taking the time to speak with me about her work and all that it entails. You provided a glimpse into a world that is rarely seen, yet has profound implications on the state of our planet, so for that, I thank you!

For even more glacier-related stories, please see Wild Jobs: Glacier Guide, Historic Photos of Glaciers from the Canadian Rockies, and Touch Ice, Take Action with Glacier Hikes and Adventures.

***

About this column:

Wild Jobs is a running series that focuses on people in outdoor-related professions. It provides a brief snapshot of their career and the duties that it entails. Please see my latest instalment, Wild Jobs: Glacier Guide, to learn more.