Mary Vaux was born in 1860 into a wealthy family in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Raised in a household that valued education, nature, and service, Mary developed an early interest in the natural world. After the death of her mother when she was nineteen, Mary assumed the role of caretaker for her younger brothers and supported the family’s shared fascination with the sciences, particularly geology and botany. The Vaux siblings began making regular expeditions to the Canadian Rockies in the 1880s, where Mary’s life would take a new direction.

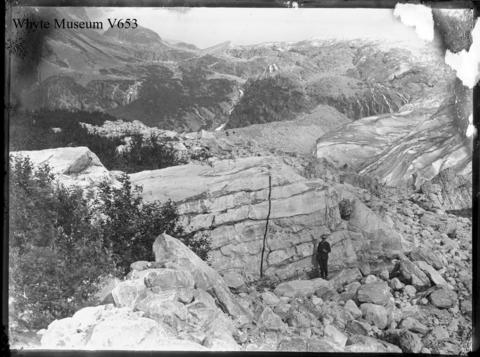

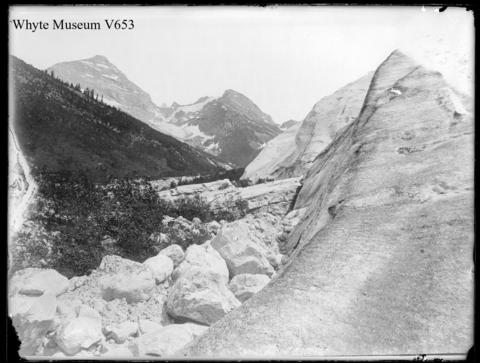

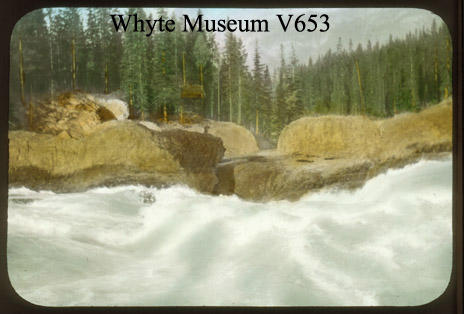

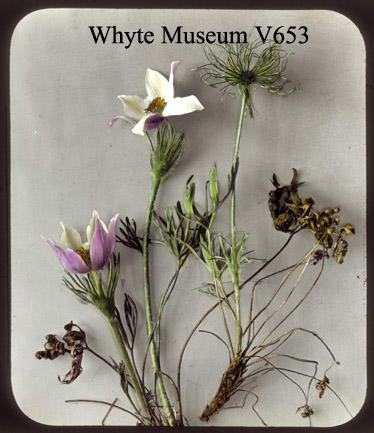

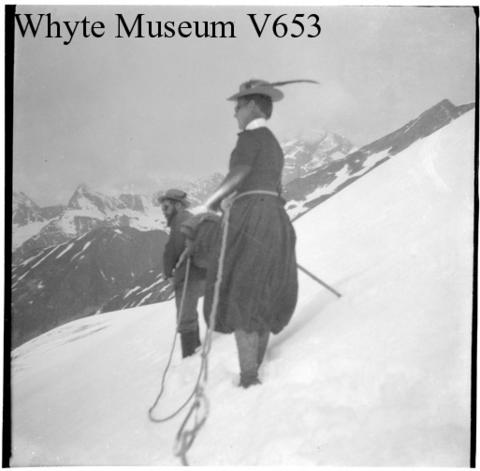

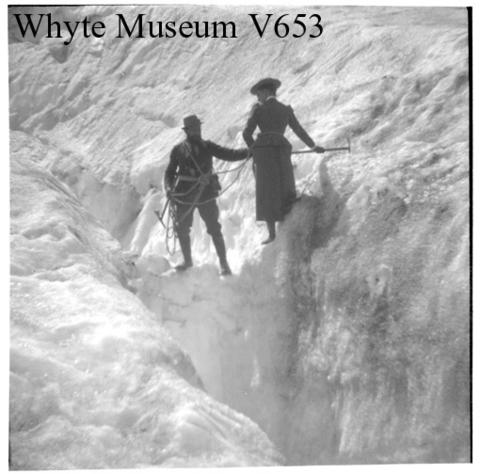

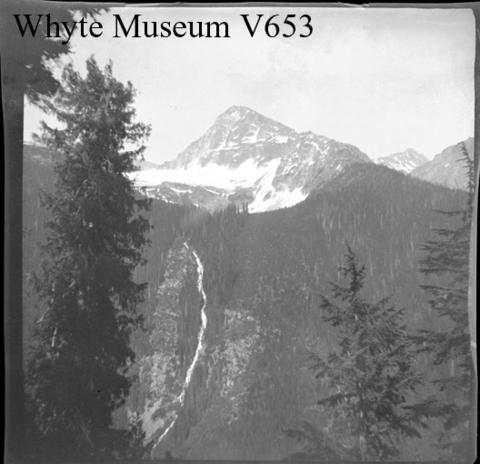

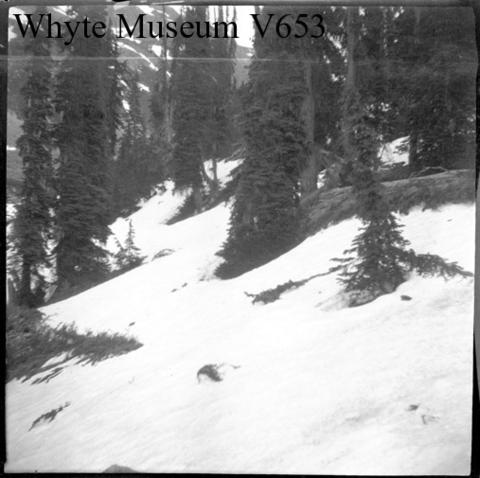

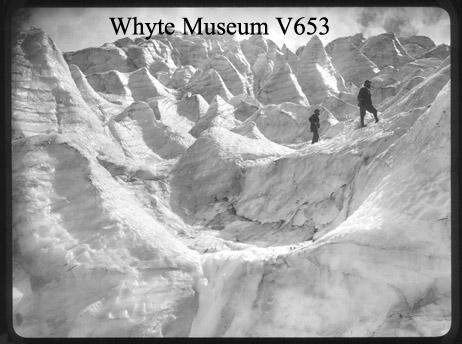

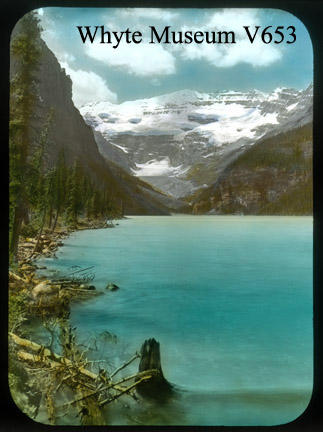

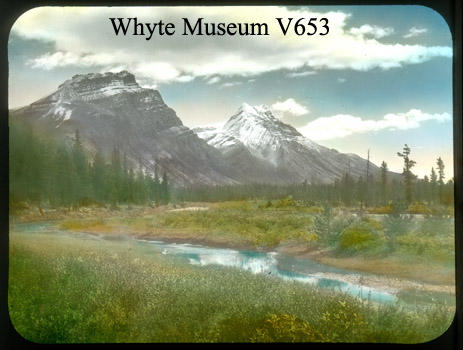

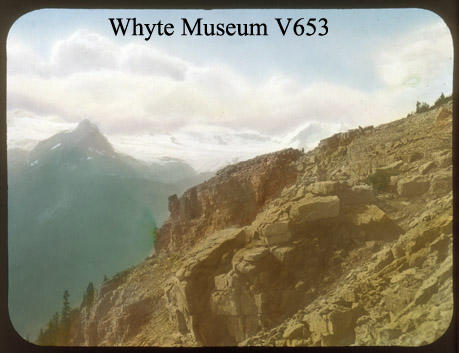

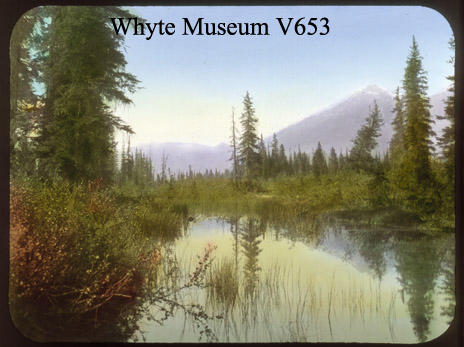

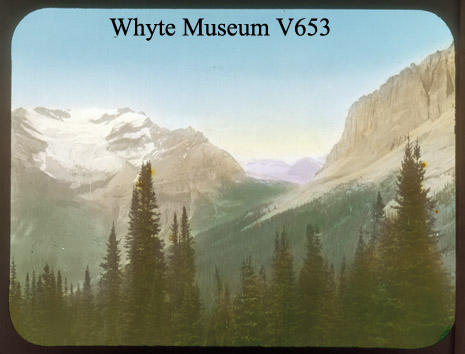

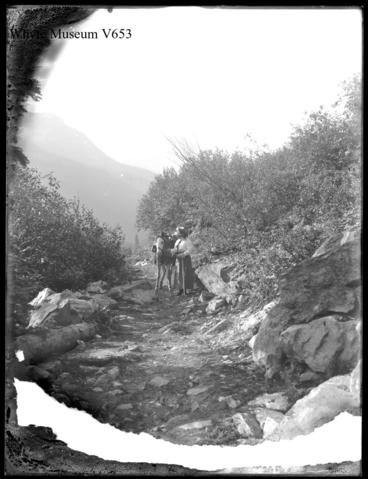

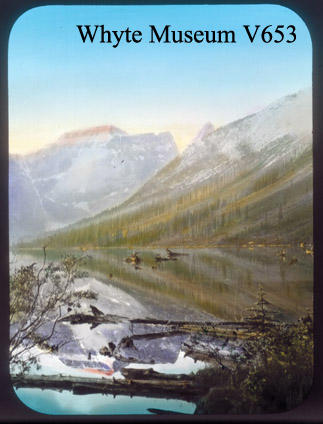

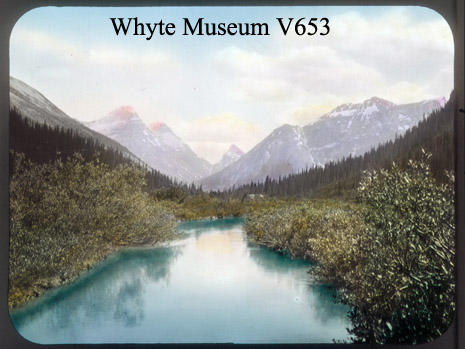

It was in the remote wilderness of what is now Banff and Jasper National Parks that Mary Vaux came into her own as a pioneering amateur glaciologist and naturalist. At a time when few women were recognized in scientific circles, Mary devoted herself to the careful study and documentation of glaciers. Over the course of more than thirty summers, she returned to the Selkirk and Rocky Mountains to photograph and measure the changes in glacial formations. Her detailed photographic work, a sampling of which can be viewed in this gallery, stands as one of the earliest systematic visual records of glacial retreat in the Canadian Rockies. She also collected and catalogued alpine flora, and her botanical illustrations earned recognition from prominent scientists of the era.

Mary’s fieldwork not only contributed to the emerging scientific understanding of climate and geology but also reflected a deep appreciation for the natural world. Her persistence and precision as a self-taught scientist broke gender barriers and helped shape public appreciation for the fragile beauty of Canada’s mountain landscapes. In 1914, she married Charles Doolittle Walcott, a distinguished paleontologist and Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. Though her marriage introduced her to elite scientific circles in Washington, D.C., she remained committed to her own pursuits and continued to return to the Rockies, even after her husband’s death.

Mary Vaux Walcott’s legacy lives on through her botanical paintings, glacier photographs, and the inspiration she offered as a woman of science in a male-dominated field. Her work not only advanced early research on climate and mountain ecology but also helped preserve the memory of a disappearing landscape.

The photos above were collected from Archives Canada. If you’re interested, additional information can be found for each photograph on their website. Stay tuned for additional posts featuring historical photos from across Alberta and Western Canada. We’d love to know what you think in the comment section below.