A popular accusation levied against Calgary is that we are engaged in “cowboy cosplay’: over-representing our Wild West roots. Calgary, after all, is a cosmopolitan city with skyscrapers, where people are more likely to work in financial services, aerospace, or retail than on a cattle ranch.

But the Wild West image is more than a homage to the Big Four (the wealthy cattleman who created the Calgary Stampede to celebrate their legacies). It can also be seen as a testament to life on the plains before the signing of Treaty 7. In many ways, the traditional image of the “cowboy”, a rugged, white, individualistic man, is actually an appropriation of a lifestyle firmly rooted in Indigenous communities.

Rodeo, popular in what today is the western United States, western Canada, and northern Mexico has many detractors who will often dismiss it as a ‘white sport”. In truth, rodeo developed from the working practices of cattle herding in Mexico. Indigenous peoples from Mexico to Canada were active participants in the creation of this sport, and continue to compete to this day.

In the early days of rodeo, from the late 1880s and up through the creation of famous rodeos such as Cheyenne Frontier Days (1897), the Pendleton Round-Up (1910), and The Calgary Stampede (1912), so-called “Indians”, Mexicans, and Black men competed alongside white men in Rodeo. Niitsitapi cowboy Tom Threepersons won the inaugural bucking bronc competition at the first Calgary Stampede. However, after WWII, control of many major rodeo competitions coalesced under The Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association or PRCA, and much of the previous diversity of the sport seemed to vanish. Indigenous peoples, unimpressed by experiences of unfair judges and timekeepers, began forming their own Rodeo Associations.

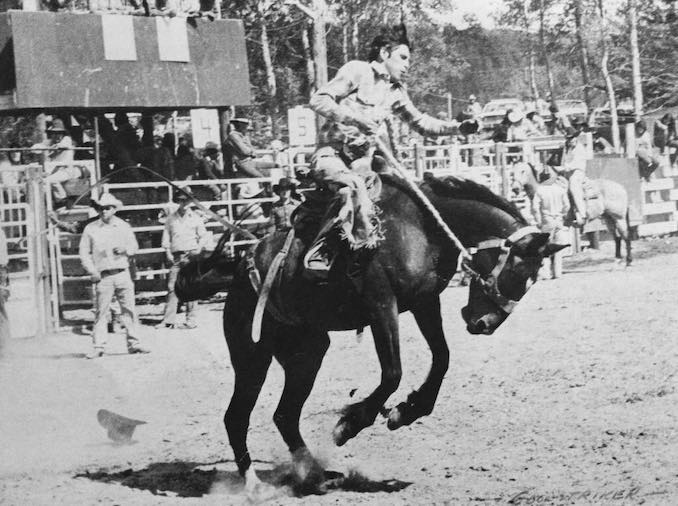

In Alberta, seven cowboys from Kainai Reserve in Stand Off, Alberta — Rufus Goodstriker, Floyd & Frank Many Fingers, Ken & Tuffy Tailfeathers, and Fred & Horace Gladstone — formed the Lazy-B 70 Rodeo Club on the reserve. Later, in 1962, this club formed the All Indian Rodeo Cowboys Association (AIRCA) for Treaty Indians. Similar stories unfolded all over North America, and in 1976 the Indian National Rodeo Finals was created.

The popularity of Indian Rodeo in Alberta actually contributed to the demise of the legendary Banff Indian Days. Non-indigenous organizers of the Banff Indian Days preferred “traditional” spectacle: parades in historical dress, the Indian Village, but the rodeo was more popular among the Nakoda participants. In the 1970s organizers cut the rodeo, claiming it didn’t appeal to tourists. This caused the Nakoda people to boycott the celebration the following year. Conflict over the purpose of the festival worsened until it disintegrated altogether.

This year in Alberta, the Siksika, Mini Thni, Tsuut’ina, Enoch, and Samson Cree nations all held qualifying events for the Indian National Finals Rodeo, along with several nations based in the US. Indian Rodeos are noted for including both senior and junior divisions in all categories, offering seniors a chance to compete well into their ‘golden years’, and stressing the multi-generation family nature of Indian Rodeo. The INFR also led the way in creating more opportunities for women to compete in rodeo, adding breakaway roping to their finals in 1991 (28 years before the PRCA).

Participation in Indian Rodeos is often a family tradition, especially for those raised on cattle ranches. “I was born to it,” recalls Duane Mistaken Chief of the Kainai Nation, of his youthful participation. “My father was the Southern Alberta Calf Roping Champion the year I was born, and I grew up on a cattle ranch. I had rodeo legends in my family. It’s just something we did.”

Judy Decoine-Wells, a Métis woman from Northern Alberta, married into a rodeo family from the Kainai Nation. She has attended the INFR finals in Vegas many times. “It’s just amazing,” she says of the experience. “We support our extended family, nephews, cousins, it fills us with pride to go down and support, to be in the stands cheering for them when they come out.”

Decoine-Wells says she enjoys making friends from all over “Indian Country” and has even been shocked to meet cowboys from her own stomping grounds up north. “One year we met a young cowboy from the Valley View area, and I thought ‘that’s a long drive!’ So now we follow his name. We always check the standings to see if he made it.”

The Indian Nation Rodeo Finals will take place this year in Las Vegas from October 22-26, and feature several cowboys from across Alberta. Bookmark the INFR website for info on next year’s qualifying rodeos in Alberta.